Elsie Dinsmore... Anne Shirley... Polly Pepper... Mary Rode...

These are heroines of Christian juvenile literature, the books thrust into little Christian girls’ hands so they wouldn’t fill their head with magic and wizards and all sorts of witchcraft that could be so damaging to little minds. These were the prescribed role models; if we can get our girls to admire these characters, to behave like these characters... well, they might not be totally perfect themselves, but at least we could look forward to punishing them less often, and convincing them to obey us without question, right?

Just do what these people do, and our lives will turn out just like theirs. When people start treating us unfairly or wrong, we just whisper a quick prayer—or better yet, one of the King James Bible verses—and the one doing the tormenting will immediately be convicted in their soul because of our behavior and ask us about God—at which time we will eloquently give a list of verses strung all together like stanzas of a poem, and they will have such respect for our vast knowledge that they will never bother us again. According to these books, even girls as young as eight years old have the capacity for complete docility and total restraint of their temper; is it really too much to expect—nay, demand—from one’s own children?

It’s Christian chick lit for little girls... and I think, for as much as I read, and as much as young girls in Christian families are encouraged (among other things) to read—and read these books, in particular—these books just about ruined my discernment, my faith, my perspective, and my life. Bear with me as I take at least four books from my early formative literary years, and unpack the deplorable fallacies in each—ones that we might not notice, for all the nice, shiny, “Sunday Best” these present on the outside.

Elsie Dinsmore

Basic Storyline: The motherless daughter of a rich Southern family comes to live with her father’s family while she waits for him to come home from abroad (since he had abandoned her mother while she was pregnant, under duress from his family—but now that the mother is dead, he can raise the child). She is dutiful, docile, incredibly saintly, and draws the admiration of everyone around her (except her own father, till the very end when she almost dies) for her spectacular character. In ensuing installments, she marries the very good friend of her father’s (which the age difference is rather suspiciously ignored and never mentioned) who of course dies and leaves her a widow—but Elsie handles it all with such purity of heart that we could never hope to achieve.

Basic Storyline: The motherless daughter of a rich Southern family comes to live with her father’s family while she waits for him to come home from abroad (since he had abandoned her mother while she was pregnant, under duress from his family—but now that the mother is dead, he can raise the child). She is dutiful, docile, incredibly saintly, and draws the admiration of everyone around her (except her own father, till the very end when she almost dies) for her spectacular character. In ensuing installments, she marries the very good friend of her father’s (which the age difference is rather suspiciously ignored and never mentioned) who of course dies and leaves her a widow—but Elsie handles it all with such purity of heart that we could never hope to achieve.

Why did we read this? Elsie is heralded as “A Christ-like role model” for little girls. There are presentations of the gospel to skeptical relatives, Bible verses illustrated, and young Elsie is the perfect example of the child every parent dreams of having: one who is devoted to the Bible, obedient in absolutely every instance, and so completely guileless that they would never be known to lie or disobey without immediate confession.

A Closer Look: This book, bluntly stated, fostered a deep discontent with my lot in life. Elsie had a big house, a rich family, and nothing but leisure outside of studies—which she never seemed to actually fail at, as the book constantly reiterated her meticulous attention to sums and lessons. I wanted people to dote on me like Elsie’s family doted on her. I wanted people to see my righteous responses and penitent tears as the pious demonstrations of a “Christ-like role model” and reward me for it. When someone teased me and I begged them to stop, I wanted them to be so ashamed of themselves that they would go above and beyond to try to make it up to me. Basically, I was a selfish little girl who would rather live in a fantasy world, and felt entirely justified in it, because Elsie was a “Christian role model” whom I was allowed to idolize and envy, because of the “excellent moral teaching” it contained.

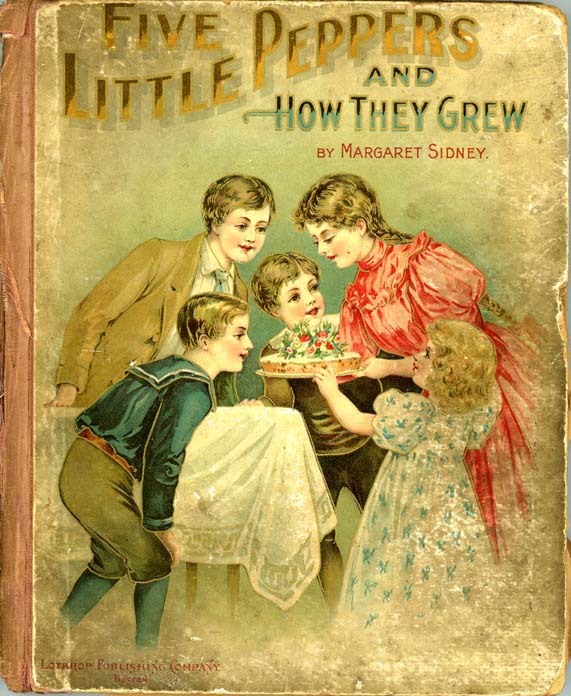

Five Little Peppers And How They Grew

Basic Storyline: A poor, rural family of six (a widowed mother raising five children under the age of 13) always manages to be happy and contented in spite of their circumstances. A chance encounter with a very rich boy brings the family into acquaintance with neighbors who are so pleased to have this poor family as friends that they become quite close—only to discover that the long-lost father of one unit in that family is the Peppers’ uncle, and so they’re not so poor after all!

Basic Storyline: A poor, rural family of six (a widowed mother raising five children under the age of 13) always manages to be happy and contented in spite of their circumstances. A chance encounter with a very rich boy brings the family into acquaintance with neighbors who are so pleased to have this poor family as friends that they become quite close—only to discover that the long-lost father of one unit in that family is the Peppers’ uncle, and so they’re not so poor after all!

Why do we read this? Five Little Peppers serves as a treatise on the importance of industry and deistic humanism (the Peppers refer to faith in God, but largely all of the difficulties are surmounted by self-effort and miraculous coincidence) served up in simple vocabulary for the early reader. Phrases like “’To Help Mother’ was the great ambition of all the children, older and younger” so cunningly emphasized, stand out to the reader’s eye, so that any child transitioning past the age of unconditional delight and into the realm of expectations and parental approval contingent on familial obligations will seize upon this opportunity and look to the lively Peppers for ideas by which they could improve their lot and take the fictional ambition as their own.

A Closer Look: It’s a family of five and the oldest is eleven years old, and everyone is just as hard-working and painstakingly pleasant as you would never believe. I read this book like the fiction it was; industry of this quiet, placid sort was not common in my world, and we certainly were never so poor that we’d go skipping around the house as a family to herald the delivery of a new stove when one arrived as a gift. Granted, it’s not as intensely tear-sodden as a certain rich young heiress... but the “family that everyone envied because they had such good times together” has little bearing on the art of actually telling a story to someone older than ten years old and home-schooled—oh, and should I also point out that there’s little about the Gospel, really, in this book... at least I wasn’t overburdened with verses in King James English, but it really felt more like a younger version of Little Women as far as a deistic, moral, poor family went—and, frankly, I prefer the Marches. They were more like my own family, and I felt I understood better how to interact with my family from reading those.

Anne of Green Gables

Basic Storyline: A Canadian couple on the small island province of Prince Edward Island send out for a boy to help the elderly man with the chores around the farm. What they get is a spunky red-headed girl who changes their life and the community of the island forever. Eight books span her life from her arrival at Green Gables, through marriage, raising seven children, two wars, and finally, seeing every one of her children happily married. (Those who survived the War, that is...)

Why do we read this? This book is popular for the nostalgia factor, maybe. Your mom grew up reading it, and it’s clean enough (prodigious and quite precocious use of the expression “Gee whiz” or some variant), and the romance is the “petty,” Hallmark variety—and there’s no divorce or really devastating severances or really illicit affairs, so everything is on the up-and-up... even if it’s miles away from the straight-and-narrow.

A Closer Look: What part of Anne’s total irreverence, her penchant for chasing after boys, lying, and her glib shallowness was ever considered a good idea for little girls to read? If Elsie Dinsmore drew me into the fantasy world of stately houses and pretty things and indolent lifestyles, Anne of Green Gables got me further in by tempting me with so many good-looking gentlemen and too-good-to-be-true coincidences and overly-forgiving authorities. (Somehow, fitting an apology into a funny story of how the mistake came about still did not get me the reaction she always managed to receive...)

Anne was disobedient, sassy, and foolish, but she was so amazing at it that everyone still loved her. I wanted that. It led me down the path of thinking that any boy who teased me secretly liked me—and did I like him too? Maybe... I mean, he is “Awf’lly handsome!” and that’s what counts, right? How could I tell? The severe lack of comfortable boy-girl relations in my youth, coupled with the profound emphasis on "moral purity" and "reserving any kind of romantic entanglements for the person you intend to marry", not to mention the stigma of "defrauding eye contact"... my whole understanding of romance was warped, and Anne Shirley didn't help at all!

A Basket of Flowers

Basic Storyline: There was an elderly basket-weaver who served his country well and saved the life of a Count who rewarded him richly. Being a devout man, however, he accepts but a little garden cottage, reasonably furnished, in which to raise his young daughter, Mary. She grows up in the company of the young Countess, their benefactor’s daughter, who is so enthralled with Mary’s skill and industry that she invites her to the castle and heaps gifts on her, which inevitably invites the resentment of her greedy, selfish lady-in-waiting, who forthwith does all within her power to discredit and frame Mary to get her first imprisoned and then banished. Together, the two make their way into the wide world where they are taken in by a kind farmer, and are able to do lots of wonderful and useful things for the farmer, and everybody is happy. By and by, the father is taken ill and dies, leaving Mary destitute and immediately afterward, she is turned out of the house by the farmer’s daughter-in-law, a prideful, shrewish woman. Mary is rediscovered by the Countess, who has by that time discovered the injustice that had separated them, and furthermore, as Mary is reunited with the people that loved her, she is able to see justice served on the cruel farmer’s wife, bestow deathbed forgiveness to the waiting-woman who wronged her, and falls in love with the judge’s son, who is both noble and exceedingly handsome, and thus the book ends with its heroine happily married.

Why do we read this? Perhaps it is to entertain the notion that life + Bible verses = eventual riches and recognition in high places. The main message seems to be something like, “No one ever says No to the Bible!” It’s a nice quiet book with lots of pithy observations, and heady theological concepts ostensibly condensed into easy object lessons for the “young reader” to understand. The evil, selfish, liar is punished; the evil, prideful tormentor ends up making a fool of herself; and the poor, oppressed heroine is eventually elevated to a place high above them all. What’s not to admire and ultimately want to have in one’s own life?

A Closer Look: Take out the bible verses, and you basically have Cinderella, Version 2. That’s all this is, a fairy tale with Bible verses thrown in. But it’s the Bible verses that make it “good Christian literature” isn’t it?

No; I’ve learned this in my own writing. Just because you have characters spouting reams of Scripture and “preach-ifying” every time they open their mouths doesn’t discount the fact that this is nothing more than a heady sermon thrust into a fairy tale with a liberal heaping of King James verses that is less a “tale for the young” and more of a sweet pat on the spiritual ego for the parent who doesn’t let their kid read C. S. Lewis' The Chronicles of Narnia “because of the Talking Animals.” (Two words: BEATRIX POTTER...)

<><><><><><><><>

The reality that these books do not address is that there will be people who will say “no” to the Bible... and do so very convincingly. There will be times that do not have a pithy verse we can carefully incise from its context and apply like a round peg to the “square hole” of our circumstances, completely verbatim and preferably in the “original” King James...for effect. It might be easy to dwell in the hypotheses of modest dresses, eligible and handsome bachelors just waiting for that saintly little angel to catch their eye, at which point they will follow them home or search the village like Prince Charming bearing only the “glass slipper” of her “shining countenance” as an identifier, of a family whose highest form of ideal amusement is sheer industry—something they will gladly spend themselves to death at the age of ten for! But what does this do for the reader in regards to their life outside the covers of the book?

One of the most poignant quotes I ever read put it this way: “Good writers touch life often...” Some people consider fiction to be merely a form of escaping one's reality, serving only to increase the disorientation upon reentry, because the “holiday” is over and the world had gone on spinning without you, and now you must play “catch-up.”

But this is not true... or rather, the “escape literature” should not be regarded as the good stuff, nor even as a reasonable sample of all fiction. Good fiction, according to the quote above, is grounded in something that the reader can relate to, ten or even fifty years down the road from when the book was published. It’s penned with a solid understanding of what life is, not one isolated Sunday-school spinster’s imagination of what life ought to be.

That is not to say that all Christian literature is bad; there exists the rare author who decides to break the mold and go ahead with telling their own kind of story that reverences God and His Word, whether or not it actually references it—all the while keeping with the truth of the quote above (which, by the way, is from Ray Bradbury’s Farenheit 451, the first “secular” novel I read of my own volition after being so jaded by the sorry state of Postmodern American Literature in my last semester of college!) and touching life often enough that the reader—far from being disoriented by the real world—is emboldened to seize the opportunities presented to her. She is inspired to appreciate her world a little more, by the way the writer presents the real-world elements of the fictional world. She is enriched in her logic and vocabulary by the quality of the amount of literature she is reading, not affixed within rigid buffers that really narrow all of literature to one or two genres because most Christian authors don’t seem to know how to fit the Gospel into anything but a romance or a children’s book.

Most of all, she is empowered to do more than just sit at home and sew and wait for her prince to knock on the door—she lives her life and engages her world because of what she has learned about it from the books she reads.

Most of all, she is empowered to do more than just sit at home and sew and wait for her prince to knock on the door—she lives her life and engages her world because of what she has learned about it from the books she reads.

No comments:

Post a Comment